A Brief History of the Mews

From equine overcrowding to luxurious living for humans

LONDON’S MEWS CHRONOLOGY

London is like no other city because in no other city will you find Mews in such prolific numbers, located so widely, or so varied.

Whilst the golden age of the Mews may only have lasted around 75 years – between 1825 and 1900 – the origins of the mews can be traced back almost 500 years. Founded in Roman times, London has since expanded in an irregular and piecemeal fashion; generally avoiding the planned and comprehensive re-building that occurred within other large cities.

London’s Mews are unique and to understand them you need to look at the key conditions that influenced the development of London, as revealed by eight significant historical events.

Perhaps the most significant of these was:

Equine Overcrowding

Mere horseplay or a harbinger of change?

Whitby Abbey ruins

1. THE DISSOLUTION OF THE MONASTERIES

For dissolution read destruction; this was Henry VIII’s action to disband monasteries and separate the Church of England from papal control after he had fallen out with the Pope over divorcing Catherine of Aragon.

When Henry VIII took this action to separate from the Roman Catholic Church it resulted in massive destruction to religious buildings and communities. Between the years 1536 and 1541 around 625 monastic communities including priories, convents and friaries were closed down. This began a process of change in land ownership as many areas of monastic land both inside and outside the city of London, were liberated from their erstwhile owners – the Church.

The Church was enormously wealthy, it owned almost 30% of the land in England and Henry needed their assets to fund his divorce. The dissolution was much criticised as it was carried out in an indiscriminate fashion that left buildings in ruins and destroyed countless English Medieval treasures of art.

It was integral to the future development of London that huge tracts of monastic land were then divided up and sold, leased or given away by Henry to his loyal courtiers and to the aristocracy. The subsequent expansion of London after the Dissolution, allowed wealthy and influential families – who would go on to build the Mews – to profit both financially and socially from development of their estates. This enabled the beneficiaries to create a lasting impression of their wealth and status. Even today it is possible to discover the legacy of these distinguished families in the names of the streets, squares and mews of London, such as Portman, Grosvenor, Cadogan

The first recorded mention of a Mews in London was in 1537, when fire destroyed Henry VIII’s stables in Bloomsbury Royal Mews which had become his royal stables. Henry then started a trend by converting the Charing Cross Mews (previously used for housing his falconry birds) to stables. He was much copied and thereafter the Mews came to have a different, more modern meaning.

2. THE CREATION OF LEASEHOLD PROPERTY OWNERSHIP

Land ownership in London differs significantly from that of other cities and countries where private landownerships are smaller and public landownerships bigger. In London large private ownerships – hereditary estates – developed because the landowners held large and substantial plots of land in one place instead of having land divided into many remote and individual freeholds. These estates were developed and then maintained using the leasehold system of land tenure, which at the beginning of the 17th century enabled landowners to allow development by others and at the same time retain an interest in the land.

Whereas a freeholder owns the building and the land it stands on in perpetuity and has ‘absolute title’, a leaseholder only has use of the land or building for a specified term of years at the end of which it has to be handed back to the landlord or be made subject of another lease. Leases therefore, provide finite periods of ownership that may be sold – they are usually for 90, 99 or 125 years, but can be as long as 999 years.

The hereditary landed estates were keen to develop their lands through the issue of building leases that, in addition to giving them overall control of ownership, allowed them to dictate the architectural style and social status of the area. Through the development of the great estates more mews were built than exist today.

Towards the end of the seventeenth century, as its population expanded, London suffered plague and epidemic as a consequence of the terrible overcrowding and the inadequate sanitary arrangements of open drains that ran down the middle of streets towards the Thames. The Great Plague of 1665, which ended in the Great Fire, resulted in 100,000 deaths.

3. THE GREAT FIRE OF LONDON

As almost every school child knows, the fire commenced in a bakery in Pudding Lane off Eastcheap, in the early hours of Sunday morning, September 2nd 1666. Due to the timber construction of houses and warehouses, it created a conflagration that raged furiously for four days. It destroyed 13,200 houses, 87 churches and 44 halls of livery. The subsequent rebuilding resulted in implementation of the first comprehensive Building Act for London in1667. This addressed the cause of the spread of the fire by changing the type of construction undertaken; legislation deemed that all buildings had to be constructed of brick or stone to protect against the possibility of fire.

The Act and those that followed contained provisions governing the relationship of house sizes to streets, also the maximum numbers of dwellings and the number of storeys per building. This form of planning is considered one of the main reasons why Georgian development, including that of the Mews, remains a success today.

4. GEORGIAN TOWN PLANNING

Perhaps the second most significant event in the historical development of the London Mews was Georgian town planning. This lay the foundations for the setting out of and construction of Mews.

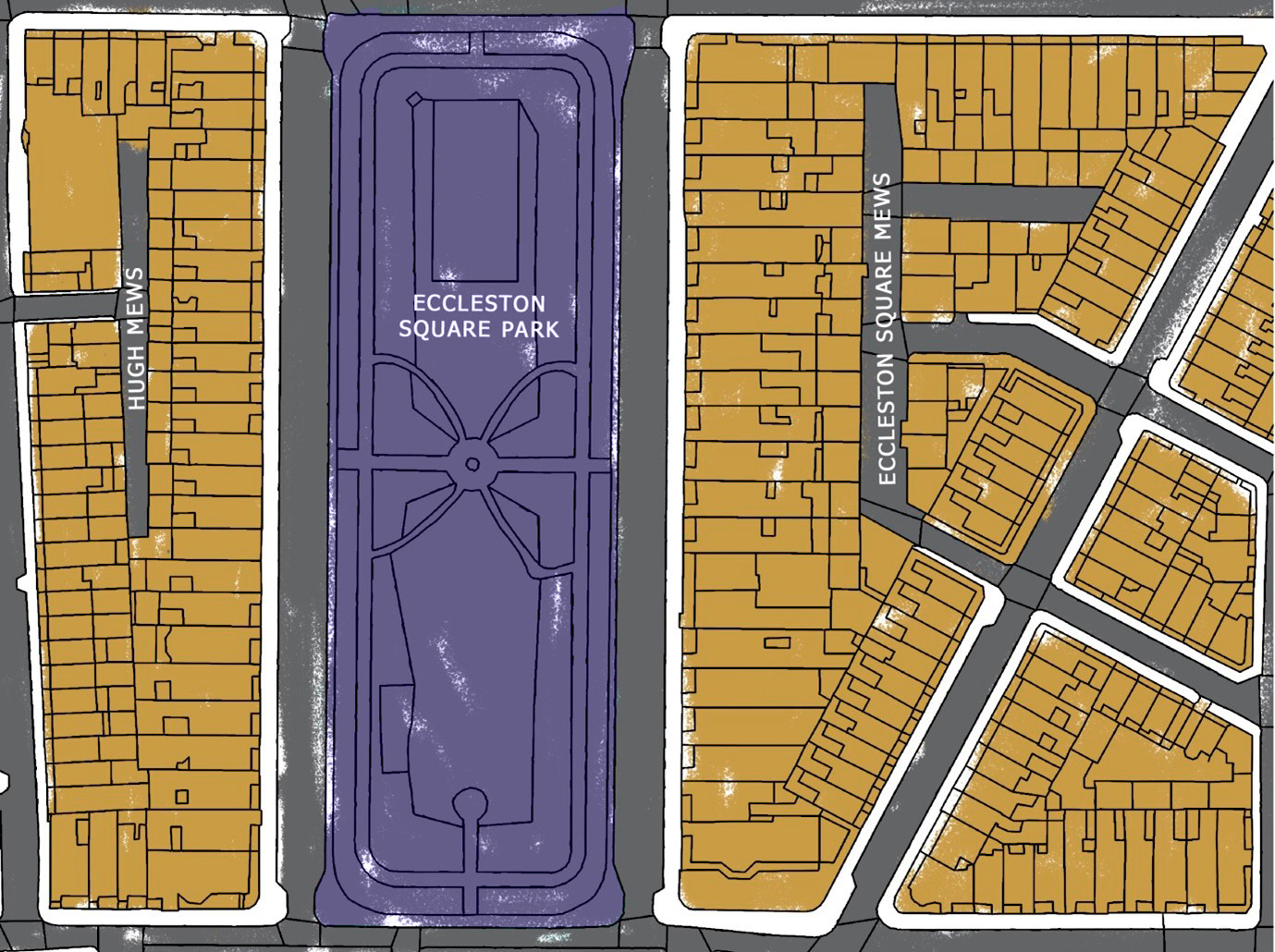

Mews in their present form were only created when London began to expand northwards and westwards into arable pasture land such as that now known as Belgravia and Mayfair. The ordered grid of streets that emerged from Georgian town planning meant that Mews could be easily and discretely contained behind the main houses in London’s most exclusive areas. Initially at least, each house had its own Mews house to the rear.

The now ubiquitous Georgian terraced houses, usually comprising four storeys including basements, were arranged in streets, squares and crescents. The terraces had an attic floor set back behind a roof parapet to accommodate servants’ quarters.

The development of the Mews was a natural progression from the private stables and livery yards that were previously on roads around London, and these buildings are now inextricably connected with the design of ‘the London House’.

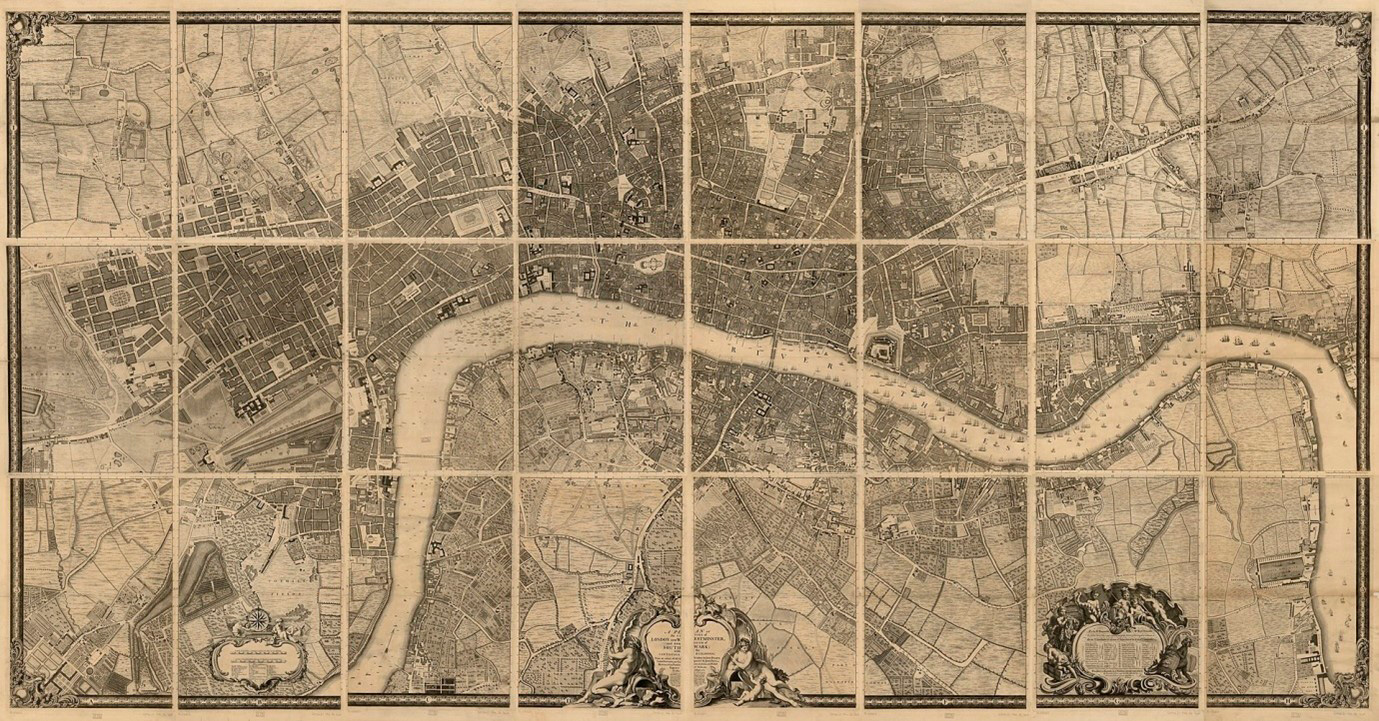

John Roque produced an engraved map in 1746 (in 24 sheets) entitled ‘A plan of the cities of London and Westminster’. This shows a number of mews located around Grosvenor Square including Shepherds, Reeves, Adams, Blackburn’s, Woods and Three Kings Yard.

For around 75 years the ideal conditions presented themselves for Mews development and if the opportunity had been ignored it is unlikely Mews would exist today.

The nineteenth century Industrial Revolution was to prove a huge success and the subsequent growth of the British Empire boosted growth of London’s population. Many people now lived in further speculative development on the established London Estates of Belgravia and Bloomsbury; many more lived in new ventures, such as the Ladbroke estate. Accommodation for horses was considered a key development criterion in building for the future.

5. VICTORIAN BUILDING BOOM

Huge increases in the numbers of houses were required for a population that nearly quadrupled in the Victorian era.

For the Mews, the period between 1825 and 1900 is the golden age of Mews construction. From the 1850’s, they were built as separate buildings at the rear of the main houses and had their own independent gates and arches. As a result, the number of mews under construction continued to increase even up until the latter part of the 19th century. The traditional use of the Mews changed as well because as households dwindled in size, and as horses and carriages were replaced with motorcars, accommodation for grooms and coachmen was no longer needed. Stables were no longer an important feature. By the end of the century the Mews growth had dramatically reduced due to:

- Migration – as fashionable people migrated to outlying areas.

- Conversion – the everchanging use of the Mews transformed from servant quarters into the smart residential addresses they are today.

Typical grid pattern of streets around Eccleston Square with Mews access from secondary streets

Victorian Building Boom

The focus had changed from new buildings to the conversion of existing Mews.

Mews that originally provided stabling and servants housing were being converted to become cottages in various styles. The coach house or stables used for garaging and the upper floors forming one or two bedrooms.

6. THE ADVENT OF THE MOTOR CAR

The 40 year period from the 1900’s to the 1940’s marked the period when Mews stopped being used as stables and became garages and houses.

People came to realise that Mews properties were ideal for conversion into terraced cottages. Widespread transformation followed – out went the equine paraphernalia, in came citizens of the metropolis.

The Survey of London cites the example in 1908 of No.1 Streets Mews changing from a stable into a dwelling house.

The Great Mews Clean Up

Isn’t it about time that filthy polluter left the Mews?

7. THE IMPOSITION OF MODERN BUILDING & DEVELOPMENT CONTROL

Prior to 1947 Town planning as we understand it now did not exist. Legislation existed in part, but was not always enforced as the machinery of local government did not support it. The general legal structure for Town and Country Planning at national and local levels was completely changed by the Town and Country Planning Act of 1947, which made planning an obligatory function and gave wide ranging powers to the County Council and Local Planning Authorities.

Whilst regulation of development was long overdue, by the 1960’s the pressure that the green belt exerted on land values was transforming urban areas. Georgian and Victorian properties were the focus for conversion as the large older type of properties were being turned from houses into flats. Areas were becoming blighted by the pressure of development as densities increased overnight and streets became filled to bursting with cars and people

Statutory protection was now needed in the form of conservation areas and listed buildings designed to conserve all that is good in the housing stock.

Around 90% of Mews are now covered by conservation area controls. Less than 10% have listed building status.

LONDON MEWS TODAY

London and its Mews have undergone remarkable changes in the last 200 or so years. It is a testimony to their adaptability that so many remain in occupation. Perhaps not by horses, but by people who utilise and adapt them to their contemporary lifestyles.

Compared to flats and maisonettes, Mews can offer more development potential as the majority are owned freehold (or their freehold ownership can be acquired). This means the owners can excavate under them to form basements. High land values in central London prompt such developments and initially, in the early noughties, they were welcomed. Basements were then being sunk by developers, who would seemingly compete with one another to go ever larger and deeper. These early excesses were met with resistance and sometimes problems. The term iceberg was coined and reflected the nature of the disproportionate magnitude of engineering works involved in extending below and out of sight of the other Mews users.

Following resistance from neighbours, planners and other interested parties, basement schemes are now necessarily more modest and are being managed more sensitively to ensure that their potential impact on the neighbours and the environment are properly mitigated.

Mews prices have risen over 500% since the 1970’s and the properties are still in considerable demand. Scores of Mews have been changed to create luxury living spaces.

No longer does the possibility of a horse sharing the accommodation still occur. There is presently only one working equine Mews in Bathurst Mews.

Bathurst Mews for sale with Lurot Brand – www.lurotbrand.co.uk/property-for-sale/house-for-sale/bathurst-mews-london-w2/7219

By the end of the century the population of London is predicted to be approximately 15 million. What will the Mews be like then… everchanging of course.

This article was written by Martyn John Brown MRICS, MCIOB, MNAEA, MARLA, MISVA of Everchanging Mews – www.everchangingmews.com who is a specialist Mews Consultant.

Everchanging Mews is owned and run by Martyn John Brown MRICS, MCIOB, MNAEA, MARLA, MISVA who provides professional advice in respect of Mews development and refurbishment projects as well as professional surveying advice – For any appraisal or advice on Mews Projects and Surveys, Valuations and Party Wall matters contact: info@everchangingmews.com or call Martyn on 0207 419 5033.